Issues around food affordability and access are clearly related to the pandemic we have been struggling with since March. However, most speakers at the webinar on Food Affordability and Access hosted by The Globe and Mailwith support from the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity identified that they are not new. (Speakers were Bob Lowe, President of the Canadian Cattleman’s Association; Gisèle Yasmeen, Executive Director of Food Secure Canada; Joshna Maharaj, chef, activist and author of a new book, Take Back the Tray; and Ellen Goddard, Gentec-associated researcher.)

The issues may be heightened, and they are affecting more people but many researchers and NGOs have been raising issues that need addressing in our food system for years. For example, the fact that Canada has a food security problem is not new, nor are the massive inequities in food security across different communities and groups – but the increase in scale of the problem associated with illness and unemployment from measures to reduce spread of the virus was unprecedented.

Overnight, the shutdown in food service, which had accounted for approximately 30% of an average household’s food budget, caused huge dislocations in how food was processed. Regulations on food preparation for food service are very different than those for retail sales to consumers in terms of packaging size and labeling, as two examples. To ensure that food products could flow to consumers through grocery stores quickly, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency relaxed some regulations on non-traditional packaging and labeling. The spread of illness within food-processing facilities caused shutdowns which, in the case of livestock, caused farm-level prices to fall and retail prices to increase, a phenomenon the public found difficult to understand and policy makers were not initially prepared for. Regulations put in place to keep employees and customers safe increased costs throughout the system. Consumers, at home for work and school, started to interact with food in different ways, including lots more cooking, storage of basic ingredients (shortages of flour) and, for many people, interest in buying direct from farmers. Whether this was driven by concerns about safety or reducing risks from long supply chains and shortages in traditional grocery is unknown.

The suddenness with which our lives changed certainly ‘inconvenienced’ some people but for the already food-insecure and the newly-unemployed, it was a massive shock. Unexpected empty shelves at the grocery store were a major surprise for the majority of Canadians who had never faced such a phenomenon. Canada’s interdependence with international markets for imports and exports became dramatically obvious. Questions as to whether we should be as dependent on foreign markets were raised by many. The use of technology throughout the food supply system, which a year earlier had seemed quite threatening to jobs, generated different attitudes when it seemed like automation and robots might be able to reduce costs associated with employees either getting ill or needing to be protected from illness and increase safety for purchasers. We all started washing our groceries when we got them home from the store by click-and-collect or by online delivery (both showing massive increases over pre-pandemic times).

As of October 2020, food prices are higher than they were in October 2019, with increases much higher than overall goods in the economy. See table for a selected set of price changes.

Consumer Price Index: % Change from October 2019 to October 2020 |

|||||

| all items | food | meat | dairy products | fresh fruit | fresh vegetables |

| 0.66 | 2.27 | 1.73 | 3.23 | 4.58 | 9.51 |

| Statistics Canada: Consumer Price Index, monthly, not seasonally adjusted | |||||

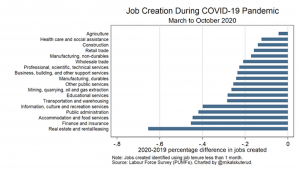

As the second phase of the pandemic in Canada surges and employment remains fragile for some, these higher food prices make life very difficult. Combining the data with data on job creation (or losses, if negative) highlights a scary picture (data charted by Prof Mikal Skuterud, University of Waterloo, skuterud@uwaterloo.ca).

Clearly the economy is fragile, and food accessibility and access is going to remain a high concern for the foreseeable future.

Although our food system did not break during the first surge of the pandemic in the spring, almost every aspect of the food system is now receiving a second look. The farming/ranching sector is concerned about a myriad of issues – from labour welfare and availability (affected by illness and restrictions on international movement of seasonal workers) to the ways in which it can be supported when disaster strikes, particularly livestock sectors with thin margins and animals that need care and feeding, and reoriented supply chains requiring changes to when and how products are marketed. From a variety of perspectives, public policy needs to consider the entire food system. We should be past focusing on conventional commercial agriculture, our food system also includes unique, local, short supply chain food systems that are critical to Canadians, and require support of a different design.

That said, Canada is in the lucky position of producing many foods efficiently and cost effectively, and we have a responsibility to export that food to the rest of the world. In an environment where logistics have been overturned by massive reductions in air traffic and difficulties with land transport for first-line workers at risk of contracting disease, significant public policy issues continue to require resolution.

Fundamentally, food security is a public policy issue that requires serious consideration in Canada. It cannot be resolved by assuming charities will take care of it, nor can charities do so in circumstances like the pandemic. Food security in Canada needs its own dedicated policies and solutions to issues as varied as access to affordable fresh food year round in the North, local food support systems and innovative food distribution systems when disaster strikes. Nutrition is a key component of health and quality of life. Canada does have the capacity to produce healthy foods for more than our own population. However we need effective food policy to address pervasive issues highlighted by the pandemic.