“At the global level, unless there’s a major technology change in how we produce food where we don’t need land, we’re going to have a food security problem fairly soon,” predicts Ted Bilyea, Former Executive VP of Maple Leaf Foods Inc. “It’s beginning to unfold in front of us.”

Ted breaks the issue down into the three A’s.

AVAILABILITY

Thirty years ago, about 12% of the world food was supplied by trade. That figure is now close to 25%. That’s pretty fragile. In Canada, we don’t have “availability” problems because 70% of what we consume is grown here, and we still export 50% of production. Our availability issue is that we’re the largest importer of U.S. processed-food in the world.

“Many of the US companies that had processing plants in Canada closed them up after NAFTA,” says Ted. “They no longer needed Canadian processing to sell here, and they already had marketing and distribution set up.

Push come to shove, we might not get everything here that we want to eat but we won’t starve to death either.

ACCESSIBILITY

“That’s when s**t happens,” says Ted. “Covid… closed border with the US… supply chain issues. Especially in the North. Solutions will involve better energy use so they can grow food themselves.”

And we need to do something about food waste. There are two sides to this: what happens before and after food items hit the store. On the before side, issues of rotting, storage, transport, etc. in the developing world can be taken care of with technology transfer, capital investment and political will. Far more troubling everywhere is the threat of disease. For example, China lost half of its hogs due to disease (mostly African swine fever) since 2018. That’s a quarter of all the hogs in the world. Just one single case of BSE (mad cow disease) in Alberta in December 2021 led China, Korea and the Philippines to ban imports of Canadian beef. An outbreak of avian flu in the US in 2015 led to the culling of 75 million poultry, and cost US$879 million to eradicate from production. These are not one-offs.

“On the consumer side, we should stop thinking of the contents of the green box as waste,” says Ted. “It’s an input to somebody else’s business in terms of upcycling. Even meat—because fats become biodiesel. So let’s be careful what we define as waste. It’s all energy in another form. If we’re doing things right, there’s no such thing as waste.”

But there’s a far more insidious issue on the horizon. Globally, we’re coming to the end of the era of abundance, convenience and perfection, food-wise. We’ve taken food for granted for too long. The shift is underway to an era where that may still be true occasionally, locally, depending on the product and location but we’re beginning to look at a future where scarcity is the more likely outcome.

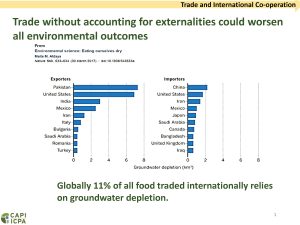

“Productivity is the best indicator of where we’re going,” says Ted. “Supply vs demand is dropping. We don’t have the global security stocks we used to have. Why? Climate change, declining R&D investment in agriculture (Alberta’s RDAR is an exception that proves the rule) and the use of non-renewable groundwater.”

*click picture to enlarge

Eleven percent of the total agriculture trade globally depends on groundwater. In the US, 64% of groundwater is used for irrigation. Fifty percent of that comes from the Ogallala aquifer. The replenishment rate of these aquifers is way down or even zero. Think California. The Ogallala aquifer will take 6,000 years to replenish. When those global aquifers run dry—and they willl!—that 11% of trade will also dry up.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Some companies will move into Canada because they value our competitive advantages. Water is one of them. Another is the prairie grasslands.

“One of the first things I learned at Canada Packers is that you can’t move the feed to the animals,” says Ted. “Most of the world is still trying to defend against that because they want to grow their own animals so they import massive amounts of corn and barley. With the emissions footprint, it makes no sense. It never did. You need tariff barriers and subsidies when you’re not competitive. Canada’s western competitive advantage is built in. We have the grass and the feed. And companies like McDonalds and Loblaws pay a premium for the sustainable beef we grow with it.”

This is, of course, where Gentec steps in and shines. Gentec’s tools for researchers (EnVigour HX™, and the new Feeder and Replacement Heifer Profit Indexes) and projects that demonstrate the value of grazing cattle on grasslands will help producers and Western Canada maintain that competitive advantage.

AFFORDABILITY

People on low or fixed income have survived this period of abundance because food was cheap. Those days are gone. Major countries are running into issues of availability. Increases in yields are slowing dramatically. We’ve brought massive amounts of land into production. That game is over. Now we’re losing land out of production due to climate change.

“If you had to pick a place to live and farm, Western Canada is a great place,” says Ted. “I see a huge demand for meat. I just wish we had more grass on which to raise more cattle with the least GHGs of anybody in the world!”