The theme of this year’s BIF symposium focuses on practical ways to make selection decisions, and genetic improvement in general, more precise and better tailored to your environment and market. The Symposium program encompasses the most recent advances in tools and technology, with a strong focus on practical application. The four-day Symposium will include world-renown Canadian hospitality, producer recognition awards, a tour of the Technology Access Centre and new meat-processing teaching facility at Olds College, a showcase of data-integrated beef production value chain, and most notably, nine scientific sessions that discuss the state of the art with regard to genetic improvement.

This month, we focus on the Young Producer Symposium and the Plenary sessions: next month, the Technical Breakout sessions and the can’t-miss feedlot tour.

YOUNG PRODUCER SYMPOSIUM AND OPENING RECEPTION – Monday, July 3

The Young Producer Symposium will take place July 3rd, 1 – 4 pm. With increasing consumer, climate, and regulatory pressures on beef production, there is a need to push the boundaries and stay ahead of the competition. Advanced technologies can provide that competitive edge; however, this level of innovation, from creation to adoption, requires purposeful investment in talent and expertise. This afternoon session for Young Producers will explore the potential for innovation in beef breeding, management, and direct sales through the lens of an innovation community.

Kicking off with learnings from the new Platform Innovation Centre, Calgary, we will hear how open social innovation is driving new technologies and increased investment in Canadian agri-tech. We will discuss how, by expanding our perspectives on what solutions and partnerships in beef production might look like, we can stay ahead of the curve in generating ideas and scaling solutions. This approach encourages collective action, and harnesses the potential for technology to solve today’s challenges. “Innovation Investment Opportunities in Ag-Tech” will explore how new technologies and innovations can be funded and implemented in agriculture. A panel of out-of-the-box thinkers and producers will discuss how they have successfully developed and implemented technology on ranch in “On-farm Innovations in Action.” The Symposium will conclude with a discussion on the value of mentorship for innovation.

This event is certainly not limited to young producers. If you have a passion for innovation and out-of-the-box thinking, if you are young at heart – this is the conversation to be a part of!

WELCOME AND SCHOLARSHIP RECEPTION

The official BIF 2023 Symposium Welcome and Scholarship Reception will be held on July 3, 5 – 9 pm at the infamous Thomson’s Social Club, Calgary Hyatt Regency.

The Calgary Hyatt Regency is on Stephen Avenue in downtown Calgary. This is ground zero for entertainment, exquisite food, and drink. Don’t let the night die young. Go out and explore!

This will be your first of many opportunities to experience true Canadian hospitality, and network with your follow BIF Symposium participants. We expect beef producers, industry leaders, and genetics extension specialists from across the globe to attend. Come reunite with old friends and make new ones. Students being awarded the Roy Wallace and Baker-Cundiff scholarships will be recognized during the reception.

Later that evening (7 – 9 pm), the National Association of Animal Breeders, the NAAB, a non-profit trade association serving the US dairy and beef artificial insemination industry, will host an information session titled “Breeding with Purpose: Using the reproductive tools available to capture value.” Dr. Ken Odde, a Kansas State University professor emeritus will discuss “Increasing Value of Steers Relative to Heifers: An opportunity for ‘Male’ Sexed Semen?”. If you’ve heard Dr. Odde before, you’ll agree that this straight shooter is worth the trip alone!

Day 1 of the BIF 2023 Symposium (at least the official program) will conclude with Mark McCully, American Angus Association CE0, and Dr. Clint Rusk, American International Charolais Association Executive Vice President, collaborating on how different reproductive tools and strategies can be used to increase the value of livestock breeding, “A Breed Perspective – Creating Tools for Desired Outcomes”.

PLENARY SESSION – TUESDAY, JULY 4, 8 – 12 PM

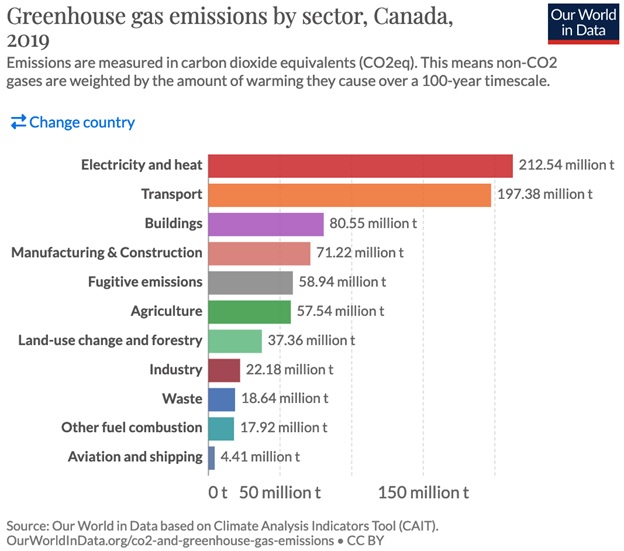

This session brings views and insight from around the globe on how we can push the needle on genetic gain. To be as precise as possible in our achievements, we need to know where we’re going. We need to define the goals we are working to achieve. This is the nexus of our first four discussions. Starting us off, Dr. Peter Amer (AbacusBio Ltd.) will walk us through formulating that breeding objective. Dr. Brian Kinghorn, Emeritus Professor, University of New England, will build on this. Dr. Kinghorn will help us consider all possible outcomes of our objectives; and talk about how selection and mating decisions become actualized goals. As the year and decades roll by, the environment will change, and genetic improvement as a mitigation tool for beef production’s environmental footprint impact holds a lot of promise. Dr. Filippo Miglior, Lactanet, will share the progress being made by the Canadian dairy industry in achieving net-zero GHG emissions by 2050. Finally, Dr. Eileen Wall from Scotland’s Rural College will discuss breeding for resiliency and adaptability because, as the environment changes, our animals will need to be adaptable, some slightly and others more so.

PLENARY SESSION – WEDNESDAY, JULY 5, 8 – 9:30 AM

Launching us into our second day of the BIF 2023 Symposium, Dr. John Crowley (AbacusBio Ltd.), will summarize Tuesday’s content on the theme of precision breeding, and set the stage for Wednesday’s talks. The session will begin with Dr. Juan Pedro Steibel, Iowa State University, addressing a rapidly-expanding topic: the use of hardware and sensors for phenomics to deliver complex data and advance animal breeding. Geoffrey Shmigelsky, CTO of OneCup AI Inc., how it couples AI and computer vision through on farm cameras to deliver a sophisticated animal monitoring and phenotyping system. Geoffrey will describe the development, validation, and challenges associated with on-farm development and deployment of this cutting-edge technology.

Advancements in Emerging Technology, chaired by Dr. Megan Rolf, Kansas State University

This session will kick off with Dr. Daniela Lourenco, University of Georgia, bringing us up to date on advancements in technology going into the generation of genomically-enhanced EPDs. Dr. Lourenco will discuss the opportunities and challenges that come with having massive amounts of genomics data being incorporated into single-step genomic evaluations as well as her take on new data sources. Next, Dr. Juan Hernandez Medrano, University of Calgary, will report on extensive studies of the impact of extreme weather on female fertility, and the role of epigenetics. Finally, Dr. Mahdi Saatchi, Iowa State University, presents RightMate from Top Genomics, and how it can improve depth and precision when evaluating the actual ability to transmit value and profit.

Advancements in End Product Improvement, chaired by Dr. Tommy Perkins, West Texas A&M University

With this session focusing on carcass, the National Beef Quality Audit (NBQA) results will be presented by Michaela Clowser, NCBA, and Dr. Jeffrey Savell (Texas A&M University). The NBQA is a comprehensive survey that evaluates efforts to improve beef quality. Conducted every five years since 1991, the checkoff-funded Audit assesses progress on a variety of production issues that ultimately affect consumer demand for beef. This session will also provide recommendations for future producer priorities.

After learning about current carcass quality results, we turn to the task of continually improving carcass quality. Dr. Andy King, USMARC, and Dr. Manuel Juarez, AAFC, will talk on the use of machine learning and a new mass spectroscopy tool “REIMS”, and the use of high-throughput phenomics to improve beef quality, respectively.

To wrap up, the session chair, Dr. Tommy Perkins (West Texas A & M University), will give an update on ultrasound guidelines and approval of new software to estimate carcass quality. The BIF Guidelines to aid producers in selecting and improving beef cattle are divided into three principal sections: Data Collection and Processing, Genetic Evaluation, and Selection and Mating.

Advancements in Genomics and Genetic Prediction, chaired by Dr. Warren Snelling, US Meat Animal Research Center

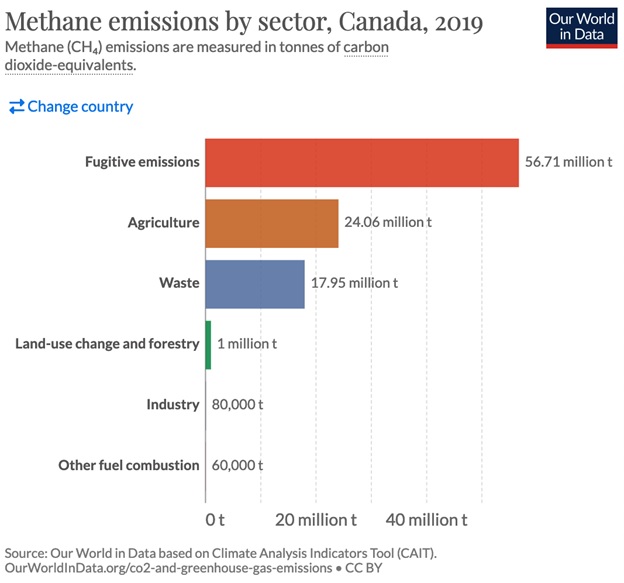

This session will feature discussions surrounding current genetic evaluations and prediction developments. Dr. Steve Miller, University of New England, will talk about current advances in genetic selection with a strong influence of observations from Australia. Dr. John Basarab, Livestock Gentec/University of Alberta, will continue by addressing non-additive genetics. Dr. Basarab will discuss studies that measure the impact of genomically-assessed heterosis on fertility, stayability, cow lifetime productivity, health resilience and GHG emissions. Dr. Snelling will present the premise and approach for rewarding high-quality data recording with higher EPD accuracies. To end the session, Dr. Kajal Devani, Canadian Angus Assoc. will present a newly-developed genetic evaluation for high immune response and cow longevity.