This year’s BIF symposium focuses on practical ways to make selection decisions (and genetic improvement in general) more precise and better tailored to your environment and market. The Symposium program encompasses the most recent advances in tools and technology, with a strong focus on practical application. It includes world-renown Canadian hospitality, producer recognition awards, a tour of the Technology Access Centre and new meat-processing teaching facility at Olds College, a showcase of the data-integrated beef production value chain, and most notably, nine scientific sessions that discuss the state of the art with regard to genetic improvement. Last month, we focused on the Young Producer Symposium, the Plenary sessions and Wednesday’s Technical Breakouts: this month, the Technical Breakout sessions on Tuesday and the can’t-miss feedlot tour.

TECHNICAL BREAKOUT SESSIONS – Tuesday, July 4, 2:30 – 5 pm

Advancements in Selection Decisions, chaired by Dr. Matt Spangler, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Dr. Larry Keuhn, USDA, will kick off this technical breakout discussing breed differences, and how to leverage these for the best outcomes. Genetic diversity has become increasingly important in the dairy industry, and this has started to reflect in the beef industry. Dr. Filippo Miglior will discuss quantifying inbreeding levels and contemplating inbreeding in selection from a dairy perspective. Dr. Troy Rowan, University of Tennessee, will bring it all together by discussing advancements in genomic technology.

Advancements in Producer Applications, chaired by Dr. Darrh Bullock, University of Kentucky

This session dives into the value of genomics and genetic selection tools, particularly from a commercial producer perspective. “Why commercial producers should be interested in genomics”, and indeed why EPDs (or even gEPDs) should be a key tool for all producers will be tackled first by Dr. Troy Rowan, University of Tennessee, and then by a panel of producers: Sean McGrath (member of Gentec’s Management Advisory Board), Harold Bayes, Paul Bennett and Donnell Brown. Gentec Director of Beef Operations John Basarab will talk in Wednesday’s genomics and genetic prediction breakout about the Gentec tools available to help producers start using genomic information (the Replacement Heifer Profit Index™ and Feeder Profit Index™: see also page 12 of The Blade for a case study). To complement, Shannon Argent from the Canadian Cattle Association Verified Beef Production (VBP+) will talk about how emerging sustainability demands can be met by genetics.

Advancements in Efficiency and Adaptability, chaired by Dr. Mark Enns, Colorado State University

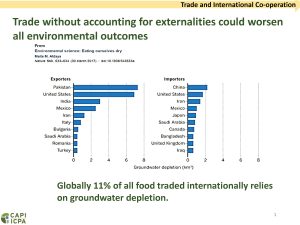

Always generating great interest, this session speaks to current profitability and sustainability drivers of selection. Dr. Megan Rolf, KSU, will present on current research around methane and feed intake, concentrating on the collection protocol for GHGs and what opportunity in the beef industry the resulting data present. Dr. Tim Holt, CSU, will speak to advancements in adaptability, with a focus on “Pulmonary Hypertension: Feedlot Heart Failure and High-Altitude Disease”. Dr. Holt has contributed to the pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) measurement guidelines for the Beef Improvement Federation, and has developed a heart-scoring system to determine levels of pulmonary hypertension and heart tissue remodelling at harvest. Dr. Scott Speidel, CSU, will expand on the topic by discussing the genetics driving those heart scores and the relationships with performance. To frame some of the talks, Dr. Justin Buchannan, Simplot, will wrap up this session and give his take on feedlot heart disease from the perspective of a vertically-integrated production chain.

Afternoon – Wednesday, July 5

OLDS COLLEGE PROGRAM, 3 – 6:30 pm

In the afternoon, there is a tour of Olds College Campus from 3 pm to 6:30 pm, which includes a visit to the National Meat Training Centre, Olds College Smart Farm, and Technology Access Centre. Additionally, there is a microbrewery and “Beef in a Global Way” tasting.

POST BIF SYMPOSIUM TOUR – Thursday, July 6, 8 – 5:30 pm

This includes a personal tour through Rimrock Feeders, one of Canada’s most cutting-edge feedlots that applies technologies such as biodigesters and roller-compacted concrete to improve production efficiency and animal health and welfare.

Travelling through the heart of Alberta’s ranchlands on the picturesque Cowboy Trail, we will also visit Hamilton Farms, a seedstock operation eager to showcase its application of genomic technology, high immune response testing, and genetic improvement through an integrated value chain and data-sharing system. UCalgary’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine will also be showcased here. Faculty members are dedicated to studying the impacts of maternal environment in beef cattle. Tour participants can expect presentations on the impact of different pain mitigation strategies after difficult calving, risk factors associated with mismothering, and the economic impact of maternal behaviour. The faculty also does a significant amount of work on disease epidemiology, and there will be presentations on the incidence of disease based on bull management practices, effective management practices to reduce preweaning calf loss and parasite control strategies.

Just west of Hamilton Farms is UCalgary’s own W.A. Ranches, a working commercial operation that allows for in-field research on calving interventions, human – animal interactions, the effects of wildlife (wild boar, for example) on cattle, bull behaviour, and calf preconditioning. The tour will include a home-raised, home-smoked Hamilton Farms beef lunch against a backdrop of our majestic Rocky Mountain range.

Kajal Devani

Canadian Angus Association