I’m not enthralled at the prospect of eating a soy-based patty or crumble that has been processed to be passed off as ‘meat’. I’m not going to consume cell-cultured ‘meat’ grown in a petri dish willingly. But I can’t wait to sink my teeth into a juicy chunk of Pinkglow® Pineapple that’s been genetically modified to stay pink and sweet. Pinkglow® Pineapple is already available in some US markets, and is an option for consumers who want to try it. Another choice that will be available within the next two years is gene-edited livestock products, including beef.

Oh dear… I’ve used the phrases genetically-modified and gene-edited. Very unpopular, unsexy and frighteningly science-y. Let’s get them out of the way.

Genetic selection has been practised in agronomy for centuries. Robert Bakewell is credited for observing that selective breeding in livestock improves the next generation. He founded the first breed associations to record pedigree and performance information. The objective was a centralized repository of data with which selection and breeding decisions could be made. That objective remains in place today.

Genetic selection was applied to crop breeding with tremendous results long before Bakewell. My favourite illustration of the power of genetic selection is the fact that modern cultivars of broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, kale, Brussels sprouts, collard greens, and kohlrabi all originate from the same Brassica oleracea plant species. Each modern cultivar was selected based on crown size (broccoli and cauliflower), leafiness (kale, collard greens) or enlarged heads of tightly-rolled leaves (cabbage, Brussels sprouts). This is the power of genetic selection; provided you have a goal and some staying power—because it takes more than one generation to get there.

GENETIC MODIFICATION

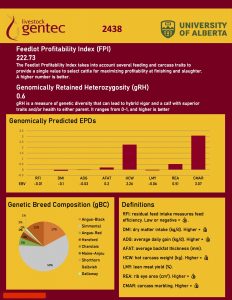

One way to “get there” sooner is to use genomics technology. In livestock, the rate of genetic improvement can be maximized by using genomically-enhanced EPDs (GE-EPDs). A different application is to modify the genetic material of organisms to generate GMOs. Two techniques are used to achieve these new, genetically-modified variants, both of which insert genetic material into an organism using a gene particle gun or a bacterial host.

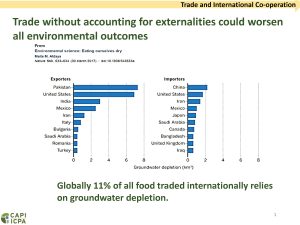

The new genetic material can be from the “original” species (changing a naturally-existing gene), it can be a gene from the same or similar species (such as AquaBounty Atlantic salmon, which was created by inserting genetic material from Pacific salmon) or from a different organism altogether (such as genetic material from the papaya ringspot virus (PRSV) used to create a papaya variant that is resistant to PRSV). Genetic modification technology has been used since the 1990s to develop varieties of tomatoes, squash, soybeans, cotton, corn, papayas, potatoes, canola, beets, alfalfa, apples, grapes—the list goes on. This technology has been used to create variants (primarily in crops) that are disease resistant, drought resistant and environmentally, economically, and ethically more sustainable. The possible advantages of genetic improvement using genomic modification technology is incredible.

One of the limitations of the technology is its precision. Peppering cells using a gene gun or using bacteria carrying the novel DNA as a kind of “Trojan horse”, doesn’t allow you to dictate where new genetic material (and sometimes what genetic material) gets inserted. Scientist have been working on a more precise technology for decades.

GENE EDITING

In 2020, Drs. Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna were awarded a Nobel prize for pioneering a revolutionary technology that improves the precision with which genetic edits can be made. Although new genetic material can be added to organisms using this technology, its true advantage comes from being able to ‘fix’ (change) existing genes. The technology, called CRISPR, has been used to create therapies for cancer, Alzheimer’s, HIV, muscular dystrophy and inherited blindness.

In agriculture, CRISPR is being used to modify crops to generate naturally-decaffeinated coffee; eggs that don’t challenge people who are allergic to egg protein; grape varieties that can grow in drought conditions, milk that is naturally lactose-free; tomatoes that are healthier or are naturally spicy; polled (hornless) Holstein cattle; tuberculosis-resistant cattle; cattle that are more heat tolerant; and pigs that are resistant to PRRS virus. Again, the list of possibilities is endless. And the development and regulatory approvals for commercialization and consumption are moving quickly, particularly in North America.

So in view of supply chain issues, labour shortages, food shortages, war and climate change… Are these products coming to market too soon or not soon enough?

Kajal Devani

Director of Science and Technology

Canadian Angus Association