“So often, at beef producer meetings, I hear people say that we need to educate the public about agriculture,” says Mike McMorris, CEO of the Ontario-based Livestock Research Innovation Corporation (LRIC). “But most consumers don’t want to be educated. They want to trust that the system functions to the highest standard. Trust being the key word.”

Animal-free protein products

Instead, in polls on why consumers find alternative proteins appealing, the answers (rightly or wrongly) focus on better human health, animal welfare and environmental health. Gaudy headlines promising Armageddon should agriculture continue in its current direction don’t help.

“That’s a pretty clear signal that people think livestock products are not better. Every producer should ask themselves how they are progressing on those three issues,” warns McMorris.

However, those issues are “wicked problems” that take time and resources, and on which the livestock sector will have to collaborate with a wide range of players (such as researchers, economists, nutritionists, veterinarians, consumers, environmentalists). To add another layer of complexity, the issues are tied to other wicked problems that may not even be on most people’s radar. McMorris and LRIC have developed a webinar and white paper on each one that we at Gentec encourage our community to check out. We also provide the potted version below.

The impacts of livestock on climate change and soil health

Globally, agriculture uses about 70% of all water withdrawn from renewable fresh water sources. The livestock industry consumes water mostly for drinking, out of which we get products such as milk, eggs and meat—and products such as urine and manure, which must be managed because they may degrade freshwater systems in several ways (E. coli, etc.) when released. Livestock are also a source of greenhouse gas emissions in the form of manure, and methane released through belching, although not to the extent you hear in the media.

“Don’t just read the headlines,” fulminates McMorris. “You’ll get the wrong story or be confused. You have to understand the context behind the numbers.”

In Canada, for example, 80% of beef cattle live most of their lives on the range and drink rainwater. In Alberta especially, they contribute to controlling invasive species on the Prairies, one of the most endangered ecosystems. That’s very different from raising livestock intensively in a feedlot—in Alberta or anywhere else—where water needs will be higher but, in the case of Australian lamb, still not affect freshwater supplies.

“For producers, knowing that each individual operation has an impact, they can find the counterpoints,” argues McMorris. “Cows burp? Yes, but they also turn unusable land into a nutritious protein for humans. Everybody’s looking for the simple answer. It’s always more nuanced.”

In his best-selling book, The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell explains how ideas spread like epidemics, little noticed until exponential growth hits a point of rapid change… and then things seem unstoppable. McMorris fears that “livestock = bad” is approaching that tipping point.

“Most consumers are generations removed from the farm, and don’t discriminate between beef cows and laying hens,” he laments. “It’s all just ‘animal agriculture’. The media often present a wrong, incomplete or biased context. The only way to avoid that is for ag groups to be proactive and collaborative in getting out messages about what we’re doing on the health, welfare and planet issues that matter to consumers.”

AMR: Antimicrobial resistance (taking a new One Health approach) and zoonoses

In Canada, 75% of antibiotics are used in animals, of which a small percentage involves pharmaceuticals of importance to humans. Canadian pharmacies and hospitals gave out 250,000 kg of antibiotics in 2016 alone. Because antibiotics are so widely used, they no longer always kill common bacteria. These resistant bacteria travel through lakes, rivers, ditches, water treatment plants, soil and landfill sites through the food chain and up to humans.

“Again,” says, McMorris, “context matters, so read deeper than the headlines. In dairy and poultry, where supply management regulates the price of the product, farmers normally work with their veterinarian and a herd health plan. Other sectors, like beef, respond to various external pressures so they are more cost conscious. The vet is as an expense.”

McMorris recommends that beef producers understand the bigger picture surrounding AMR, that they track their use of antibiotics, dispose of excess product safely, and follow the treatment according to the label and the vet.

AMR is the quintessential wicked problem that binds us all together. Although some consumers are willing to pay a small premium for products that are certified “raised without antibiotics,” thinking they are helping with AMR, few realize that withholding antibiotics from sick animals is a terrible welfare strategy, putting the whole herd, and ultimately humans too, at risk of infection. Good intentions don’t cut it.

One of the great fears is that some bacteria will eventually resist even the most powerful antibiotics reserved for human use. Should that happen, we can expect more animal-to-human and human-to-animal transfer of disease (zoonoses). COVID-19 is the mother of all zoonoses (so far); others include rabies, salmonella, Ebola, encephalitis from ticks and Lyme disease.

Part of the answer lies in the JUDICIOUS use of antibiotics, which requires compromise by all parties. Another part lies in thinking globally. As COVID-19 has taught us, variants can appear anywhere, at any time. Being vaccinated in Canada isn’t enough. All the world’s citizens need to be vaccinated for the response to be effective. It’s the same on the farm, especially since animals and products move around a lot and are exported. Producers must have thorough biosecurity that includes people, family and pets as well as the more obvious delivery trucks, feed and farm machinery.

Genetics

Humans have used genetics in agriculture from its earliest days to create products they want; the development of corn from a weedy grass into the powerhouse we know today is good example. Whereas breeding used to be done by “eye”, now we have technology, databases and tools such as CRISPR to help out. The rationale is still the same: deliver affordable, nutritious food to 7.8 billion hungry mouths.

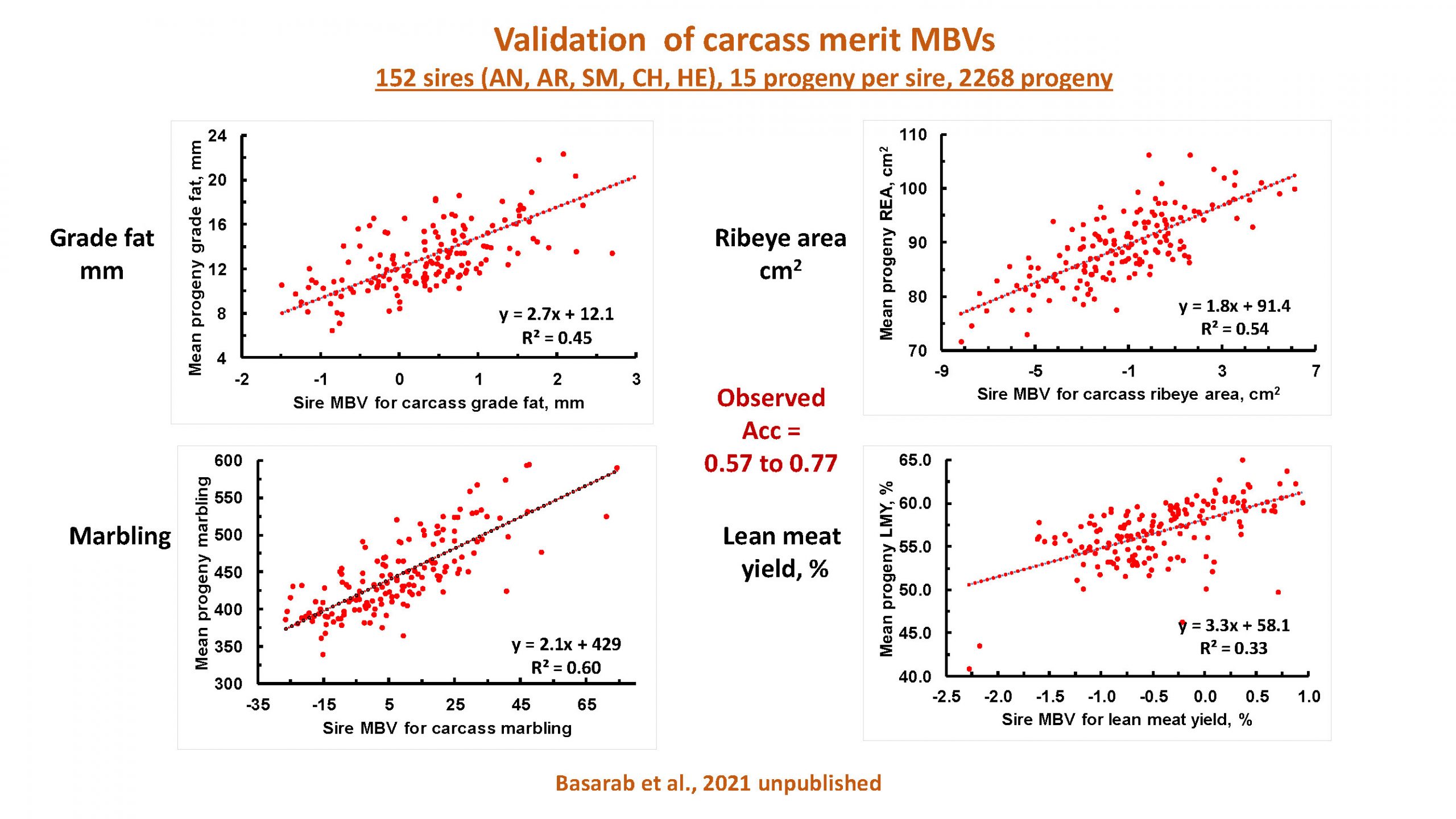

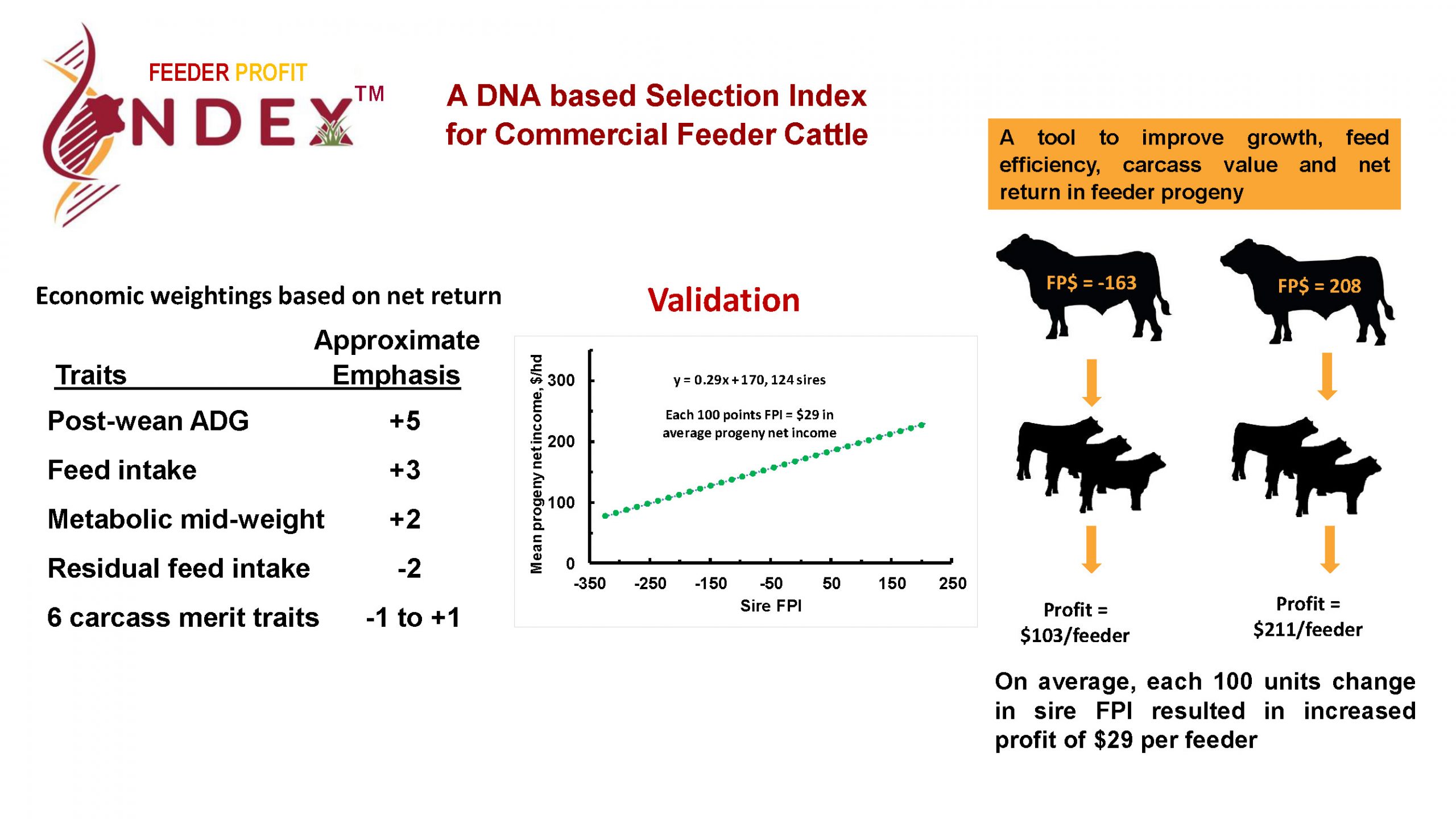

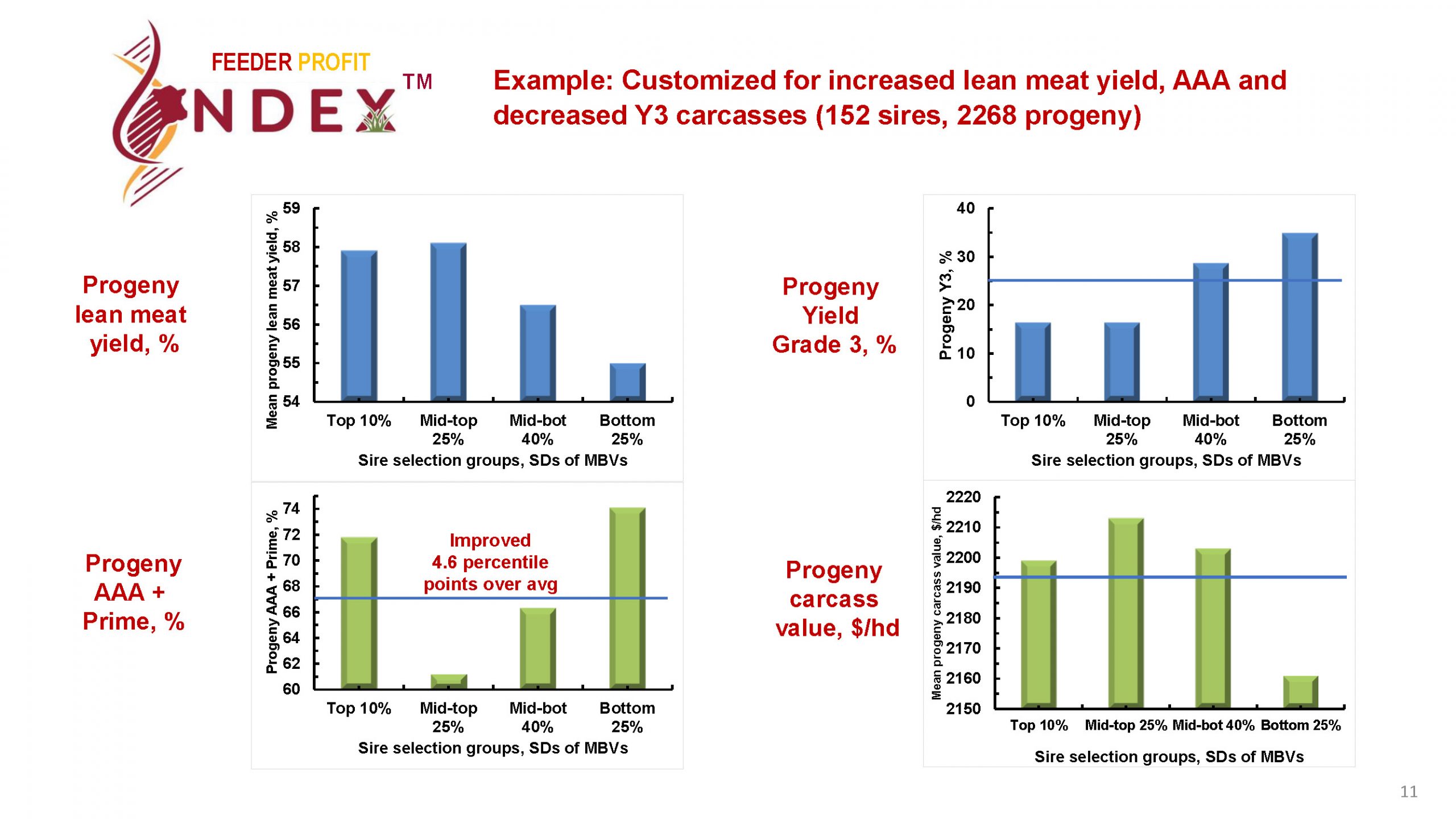

Genetics has made incredible differences to the dairy sector. For example, milk yields have increased, butterfat has increased and decreased according to demand, polled (hornless) cows have improved farm safety and reduced injuries. The beef sector has not benefitted from genetics to the same extent. Cow calf producers are interested in the longevity of the cow, a live calf on the ground every year. Feedlot producers want daily gain, marbling; and packers want a big carcass. And consumers want low cost, sustainable production and good animal welfare. The Canadian Beef Improvement Network (CBIN) was launched to help derive the benefits of genetics for the entire beef supply chain, always with a key focus on the consumer.

“The Gene: An intimate history should be required reading,” says McMorris. “It’s about mankind’s understanding of genetics from 5,000 years ago to today with some thoughts about the future. Today, genetic technologies are incredibly powerful, and we all need some understanding to develop well thought-out positions on what parts of it we will and will not use—in humans and in agriculture. Right now, there are a lot of uninformed people with strong opinions.”

Many years ago, a staff member at the Elora Beef Research Station told McMorris that, given a chance to start over, he’d take Psychology at university instead of Animal Science because he finally realized that when you get out into the world and see how things work, it’s all about people.

“That’s why, on genetics and all the other Big Things, the livestock sector needs consistent, informed, collaborative messaging. Because we have to connect with people.”

“We all need to change a little bit,” concludes McMorris. “Life is changing fast. We can be part of that change and help to create the future—or risk becoming a victim of what others decide.”

, owner/operator of Lazy A Farms Ltd. and Chair of Gentec’s Management Advisory Board. “Number One is the 50,000 independent cattle farms with an average of 70 cows on each one. This complex community is very difficult to motivate to adopt new technology.”

, owner/operator of Lazy A Farms Ltd. and Chair of Gentec’s Management Advisory Board. “Number One is the 50,000 independent cattle farms with an average of 70 cows on each one. This complex community is very difficult to motivate to adopt new technology.”